Giotto mission

Artist's concept of Giotto spacecraft |

|

| Operator | European Space Agency |

|---|---|

| Mission type | Fly-by |

| Flyby of | Comet Halley, Comet Grigg-Skjellerup, Earth |

| Flyby date | (Halley) 14 March 1986, (Grigg-Skjellerup) 10 July 1992 |

| Launch date | 2 July 1985 |

| Launch vehicle | Ariane 1 rocket |

| Mission duration | Ended on 23 July 1992 |

| COSPAR ID | 1985-056A |

| Homepage | Official site |

| Mass | 582.7 kg |

| Power | 196 W |

| Orbital elements | |

| Periapsis | 596 km (Halley), 200 km (Grigg-Skjellerup) |

Giotto was a European robotic spacecraft mission from the European Space Agency, intended to fly by and study Halley's Comet. On 13 March 1986, the mission succeeded in approaching Halley's nucleus at a distance of 596 kilometers. The spacecraft was named after the Early Italian Renaissance painter Giotto di Bondone. He had observed Halley's Comet in 1301 and was inspired to depict it as the star of Bethlehem in his painting Adoration of the Magi.

Contents |

Mission

Originally a United States partner probe was planned that would accompany Giotto, but this fell through due to budget cuts at NASA. There were plans to have observation equipment on-board a Space Shuttle in low-Earth orbit around the time of Giotto's fly-by, but they in turn fell through with the Challenger disaster.

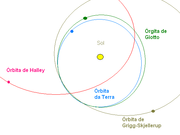

The plan then became a cooperative armada of five spaceprobes including Giotto, two from the Soviet Union's Vega program and two from Japan: the Sakigake and Suisei probes. The idea was for Japanese probes and the pre-existing American probe International Cometary Explorer to make long distance measurements, followed by the Russian Vegas which would locate the nucleus, and the resulting information sent back would allow Giotto to precisely target very close to the nucleus. Because Giotto would pass so very close to the nucleus ESA was mostly convinced it would not survive the encounter due to bombardment from the many high speed cometary particles. The coordinated group of probes became known as the Halley Armada.

The craft

The spacecraft was derived from the GEOS research satellite built by British Aerospace, and modified with the addition of a dust shield as proposed by Fred Whipple which comprised a thin (1 mm) aluminium sheet separated by a space and a thicker Kevlar sheet. The later Stardust spacecraft would use a similar Whipple shield. A mock up of the spacecraft resides at the Bristol Aero Collection hanger, at Kemble Airport, UK.

Timeline

Launch

The mission was given the go-ahead by ESA in 1980, and launched on an Ariane 1 rocket (flight V14) on 2 July 1985 from Kourou. The craft was controlled from the European Space Agency ESOC facilities in Darmstadt (then West Germany) initially in Geostationary Transfer Orbit (GTO) then in the Near Earth Phase (NEP) before the longer Cruise Phase through to the encounter. While in GTO a number of slew and spin-up manoeuvres (to 90 RPM) were carried out in preparation for the firing of the Apogee Boost Motor (ABM), although unlike orbit circularisations for geostationary orbit, the ABM for Giotto was fired at perigee. Attitude determination and control used sun pulse and IR earth sensor data in the telemetry to determine the spacecraft orientation.

Halley encounter

The Soviet Vega 1 started returning images of Halley on 1986 4 March, and the first ever of its nucleus, and made its flyby on 6 March, followed by Vega 2 making its flyby on 9 March.

Giotto passed Halley successfully on 14 March 1986 at 600 km distance, and surprisingly survived despite being hit by some small particles. One impact sent it spinning off its stabilized spin axis so that its antenna no longer always pointed at the Earth, and importantly, its dust shield no longer protected its instruments. After 32 minutes Giotto re-stabilized itself and continued gathering science data.

Another impact destroyed the Halley Multicolor Camera, but not before it took spectacular pictures of the nucleus at closest approach.

First Earth flyby

Giotto's trajectory was adjusted for an Earth flyby and its science instruments were turned off on 1986 15 March at 02:00 UT.

Grigg-Skjellerup encounter

Giotto was commanded to wake up on 2 July 1990 when it flew by Earth in order to sling shot to its next cometary encounter.

The probe then flew by the Comet Grigg-Skjellerup in 10 July 1992 which it approached to a distance of about 200 kilometres. Afterwards, Giotto was again switched off on 23 July 1992.

Second Earth flyby

In 1999 Giotto made another Earth flyby but was not reactivated.

Results

Scientific results

Images showed Halley's nucleus to be a dark peanut-shaped body, 15 km long, 7 to 10 km wide. Only 10% of the surface was active, with at least three outgassing jets seen on the sunlit side. Analysis showed the comet formed 4.5 billion years ago from volatiles (mainly ice) that had condensed onto interstellar dust particles. It had remained practically unaltered since its formation.

Measured volume of material ejected by Halley:

- 80% water,

- 10% carbon monoxide

- 2.5% a mix of methane and ammonia.

- Other hydrocarbons, iron, and sodium were detected in trace amounts.

Giotto found Halley's nucleus was blacker than coal, which suggested a thick covering of dust.[1]

The nucleus's surface was rough and of a porous quality, with the density of the whole nucleus as low as 0.3 gram per cubic centimetre (g/cm³).[1] Sagdeev's team estimated a density of 0.6 g/cm³,[2] but S. J. Peale warned that all estimates had error bars too large to be informative.[3]

The quantity of material ejected was found to be 3 tonnes per second[3] for seven jets, and these caused the comet to wobble over long time periods.[1]

The dust ejected was mostly only the size of cigarette smoke particles, with masses ranging from 10−20 kg[3] to 40x10−5 kg (10 attograms to 40 milligrams). (See Orders of magnitude (mass).) Although the one particle impact that sent Giotto spinning was not measured, from its effects - it also probably broke off a piece of Giotto[3] - its mass has been estimated to lie between 0.1 and 1 gram.[1]

Two kinds of dust were seen: one with carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen and oxygen; the other with calcium, iron, magnesium, silicon and sodium.[1]

The ratio of abundances of the comet's light elements excluding nitrogen (ie. hydrogen, carbon, oxygen) were the same as the Sun's. The implication is that the constituents of Halley are among the most primitive in the solar system.

The plasma and ion mass spectrometer instruments showed Halley has a carbon-rich surface.

Spacecraft achievements

- Giotto made the closest approach to Halley comet and provided the best data for this comet.

- Giotto was the first spacecraft to provide pictures of a cometary nucleus.

- Giotto was the first spacecraft do a close flyby of two comets. Young and active comet Halley could be compared to old Grigg-Skjellerup.

- Giotto was the first spacecraft to return from interplanetary space and perform an Earth swing by.

- Giotto was the first spacecraft to be re-activated from hibernation mode.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 "ESA Science & Technology: Halley". ESA. 2006-03-10. http://sci.esa.int/science-e/www/object/index.cfm?fobjectid=31878. Retrieved 2009-02-22.

- ↑ RZ Sagdeev; PE Elyasberg; VI Moroz. (1988). "Is the nucleus of Comet Halley a low density body?". AA(AN SSSR, Institut Kosmicheskikh Issledovanii, Moscow, USSR), AB(AN SSSR, Institut Kosmicheskikh Issledovanii, Moscow, USSR), AC(AN SSSR, Institut Kosmicheskikh Issledovanii, Moscow, USSR). http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1988Natur.331..240S. Retrieved 2007-05-15.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 S. J. Peale (November 1989). "On the density of Halley's comet". Icarus 82 (1): 36–49. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(89)90021-3.

External links

- Mission website

- Interview with the mission's Deputy Project Scientist by NASA's Solar System Exploration

- Nature 1986 about Giotto mission

- Giotto di Bondone's 'Adoration of the Magi' painting that includes his rendition of Halley's Comet

|

|||||